The US Air Force (USAF) at the end of 1967 started to air-drop around 20,000 micro sensors into a country bordering Vietnam to be monitored by an IBM mainframe, in order to help direct US airstrikes. The project was an expensive disaster that became a foundation for US domestic military surveillance of non-whites.

It had little impact (e.g. “sensors couldn’t tell the difference between a gun and a shovel”) while costing American lives. All it did prove was the fact that drones flying above a mesh of sensors could launch airstrikes on a moment’s notice…for a low low price of just $1 billion/year in the 1970s, as the following documentary puts plainly:

When you stop to think about it if you have $30M orbiting reconnaissance aircraft to transmit signals, and $20M command post to call in four $10M fighters to assault a convoy of five $5000 trucks with $2000 worth of rice, it’s easy to see that’s not cost-effective. This is a self-inflicted wound… a losing proposition…

Initial Plans

The North Vietnamese had built a network of roads through neighboring neutral countries Laos and Cambodia to supply forces in South Vietnam. This “Truong Son Road” (called “Ho Chi Minh Trail” by Americans) was concealed by the natural foliage of thick jungle.

Plans were concocted by Americans to appear respectful of Laos and Cambodia, while still bombing them, by secretly dropping hidden sensors that would guide targeted strikes and Army Special Forces teams “over the fence”

The idea of constructing an anti-infiltration barrier across the DMZ and the Laotian panhandle was first proposed in January 1966 by Roger Fisher of Harvard Law School in one of his periodic memos to McNaughton.

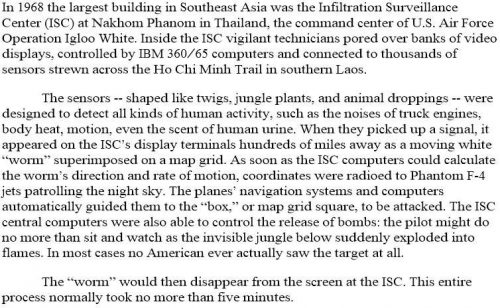

A book called The Closed World explains in detail what these Harvard Law School plans turned into:

Sensor Technical Details (Data Integrity Failure)

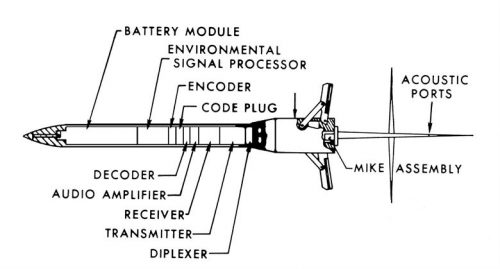

There were several iterations of the sensors. The USAF archives refer to these categories:

- ADSID I and III, (Normal) and (Short): (Air Delivered Seismic Intrusion Detector) – transmitted vibration from geophone (personnel or vehicles in motion)

- HELOSID (Helicopter Delivered Seismic Intrusion Detector)

- ACOUSID II and III: (Acoustic and Seismic Intrusion Detector) – transmitted sound from microphone

We’re talking here about $2K radios inside a dart-shaped canister with a 2 week battery (later expanded to 45 days by changing from continuous to polling), and a 20% failure rate on deployment.

Ten years ago Air Force Magazine described the wide set of problems with false positives from these wireless sensors in a jungle. This honest analysis is a far cry from how the USAF originally fluffed up the technology to be as easy as “drugstore pinball” and give North Vietnamese “nowhere to hide”:

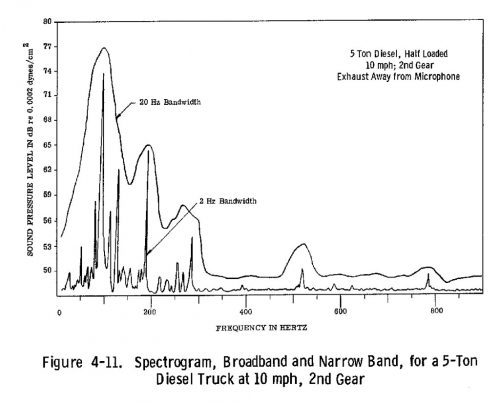

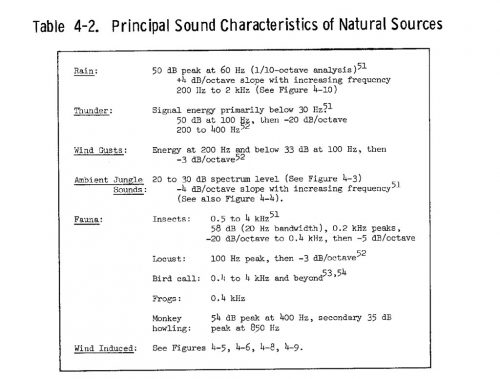

The challenge for the seismic sensors (and for the analysts) was not so much in detecting the people and the trucks as it was in separating out the false alarms generated by wind, thunder, rain, earth tremors, and animals—especially frogs.

There were other kinds of sensors as well. One of them was the “people sniffer,” which chemically sensed sweat and urine.

[…]

“We wire the Ho Chi Minh Trail like a drugstore pinball machine, and we plug it in every night,” an Air Force officer told Armed Forces Journal in 1971. “Before, the enemy had two things going for him. The sun went down every night, and he had trees to hide under. Now he has nothing.”

Here are the sort of acoustic details captured in working group studies hoping to isolate signals of frogs and shovels from soldiers and trucks:

Sensor Deployment

Either a F-4 Phantom jet, a OV-10 Bronco plane, or a CH-3 Jolly Green Giant helicopter was used for air drops. Given the large quantity of sensors, frequency of drops, size of budget and talent of engineering, their placement wasn’t as sophisticated as one might imagine.

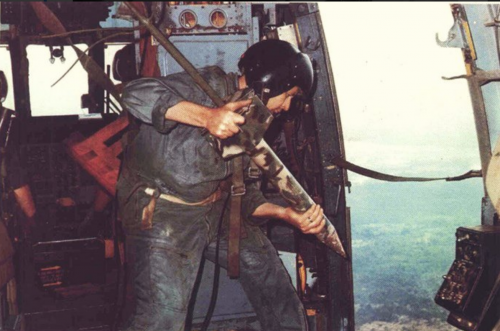

Here you can see a member of 21st Special Operations Squad (SOS) based in Nakhon Phanom (under the Dust Devils call sign) at low altitude sending a sensor by hand.

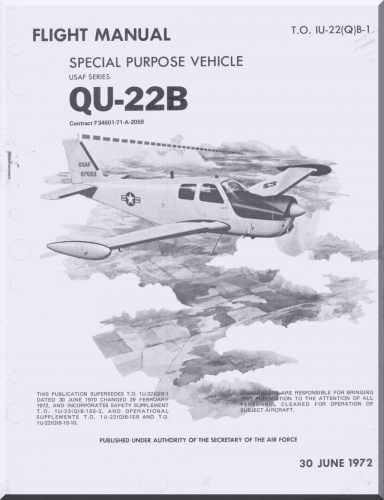

Initially MC-130E Blackbird were used to orbit and monitor the sensors. The 554th Reconnaissance Squad (under the Vampires call sign) by 1970 started orbiting a QU-22B “drone” to pick up signals from the sensors and relay them back to Infiltration Surveillance Center (ISC) at the Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base.

Despite being engineered with complex electrical equipment to enable remote control. reliability failures meant every flight carried a pilot on board (A QU-22 reunion site interviews them).

The high-tech QU-22 drone program was cancelled after just two years with a number of crashes including two inside Laos.

Command Center

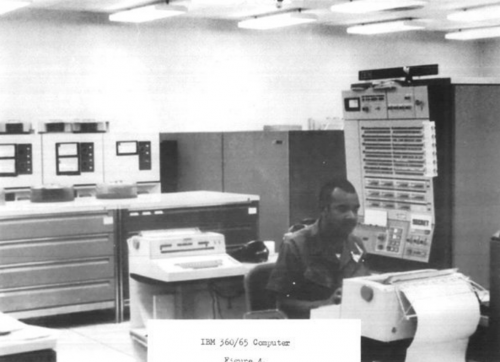

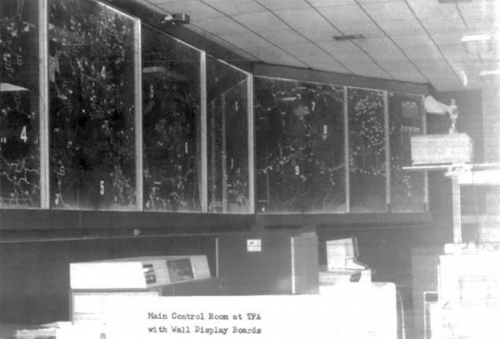

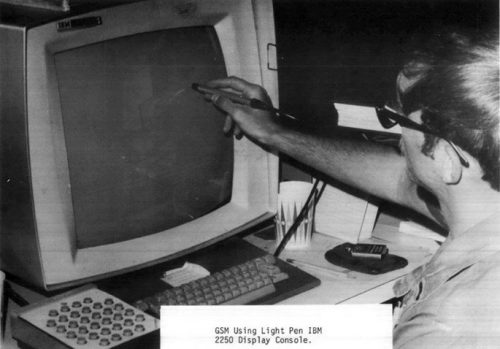

Back at the ISC, computers made by IBM were connected to a giant wall-sized display of the area under surveillance, as well as touchscreen monitors (images from US Air Force Historical Research Agency):

Military Surveillance “Toys” Deployed in America

Despite President Nixon’s backing, the expense of Igloo White coupled with many American casualties sat on top of a failure to produce results to justify continuing the program, especially after North Vietnamese simple changed tactics. The program was cancelled by 1973 just as Nixon was infamously announcing he would criminalize being non-white.

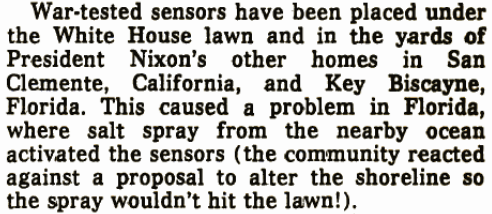

Nixon had believed so strongly in the new surveillance technology that he had the same sensors deployed to his lawns and…of course the border with Mexico.

Needless to say, even domestically the systems failed spectacularly as documented in 1971 and reported again in 1972:

That kind of outcome didn’t seem to dissuade some from thinking there is a bright future for military surveillance technology along America’s borders.

In 1989 the Air War College reported that military surveillance failure under Nixon on the border with Mexico meant President Reagan actually had a useful foundation for military role in the criminalization of non-whites.

Reagan pushed so hard on invasive of domestic military surveillance the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 was modified “to allow all branches of the Armed Forces to provide equipment, training, and assistance to the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Customs, and to other Drug Enforcement agencies”. Today it is widely known and becoming uncontroversial that the “war on drugs” was intentionally racist — criminalizing non-whites.

Conclusion

The true lesson from Igloo White was that an expensive technological military replacement (even domestically) for human intelligence gathering systems may have been very fast yet also very expensive and never really proven accurate. It will forever be known in history as a “self-inflicted wound” by Nixon that Reagan doubled-down on.

Air Force Magazine, while admitting the USAF vastly overstated the success of their work, also emphasized analysis of data can be mishandled by everyone involved:

…7th Air Force’s “numbers game” was refuted by the CIA’s own “highly reliable sources,” referring to its agents in the enemy ranks. The CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency developed a formula that arbitrarily discounted 75 percent of the pilot claims. […] Then, as now, the bomb damage assessment process was flawed on both ends: Operations tended to claim too much; Intelligence tended to validate too little.

It was the “fire, ready, aim” foreshadowing of today’s drone programs (e.g. Operation Haymaker) where the vast majority of targets are later reported to be innocent civilians.

* “Bugging the Battlefield” by National Archives and Records Administration, 1969:

For a perspective from the Laotian side, see “The Rocket”:

Update April 2021: Jim Bolen (former Special Forces operative in Laos and Cambodia on SOG operations to the Ho Chi Minh and Sihanouk Trails during the Vietnam War — recon team leader on over 40 SOG missions and extracted under fire from over 30) gives a new interview where he describes “Reconnaissance Missions to the Ho Chi Minh Trail” and argues that electronic sensors were infallible technology and instead it was LBJ who wasn’t listening.

…we had planted electronic seismic sensors along the Trail coming out of North Vietnam. These sensors were monitored 24 hours a day 365 days a year by C-130 Blackbirds. The seismic sensors would pick up vibrations from truck or tank movements along the Trail.

Sensors dropped along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Attapeu Laos. Source: Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group

Update October 2021: Declassification of secret missions gives us the opposite of Jim Bolen, “MACV-SOG: A Conversation with John Stryker Meyer“, which includes a gold nugget of modest wisdom from a Green Beret who served on the ground at the time that the bombing campaigns in Laos were “completely useless“.