There are many, many versions of the January 8, 1815 Battle of New Orleans. None of them, so far, seem to tell the history in a manner that would be most fair to the participants.

Most ignore completely the most important detail:

American forces were made of “free men of color”. Specifically, of the 1,000 Louisiana militia and volunteers in the battle, it was nearly 50% non-white. The U.S. Army even has a print set called “The American Soldier” with a depiction of a the free men of color battalion in action to celebrate this fact.

An example of a site that does mention the “men of color” soldiers is the Tennessee Historical Society.

[Jackson] included a large number of both free men of color and enslaved black men in and around the city. To recruit the former, Jackson promised them the same wages and, equally important, the same respect as their white compatriots — a unique opportunity for black and Creole residents living in a Southern city committed to white racial superiority. For those enslaved, he appealed to their desire for freedom.

Take a moment to question the statement New Orleans was “committed to white racial superiority”. Lacking any citation at all, it sounds suspicious to me for a city known to be highly diverse in the 1800s.

Although it is true that New Orleans brutally put down a huge slave revolt in 1811, the free men before and afterwards still were present and exercising their rights up until America started shutting them down.

A good resource on this is the Louisiana Digital Library: Free People of Color collections, which is full of first-person materials as well as insights such as “white soldiers were thought cheaper than Negro slaves” as well as statements like “all the difference between a free man of color and a slave, that there is between a white man and a slave”.

During both Spanish and French rule of the colony of Louisiana the “free men of color” regularly served in militias. So when the U.S. took over New Orleans, it started with an integrated military.

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, about 16% of the roughly 8000 people living in New Orleans were free people of color. The first official U.S. census of the Orleans Territory in 1810 counted 7,585 free persons of color, or about 10% of the total population.

Remember how above I mentioned 50% of Jackson’s force from Louisiana was non-white? That’s a huge jump up from being just 10% of the population.

The above quote from the Tennessee History site is followed-up soon after on the same page by another odd statement:

Jackson not only ordered all black troops out of New Orleans at the behest of white residents who were fearful of armed black city-dwellers; he also reneged on his offer to free his enslaved troops and instead, ordered them to return to their slave-owners.

Let me try to untangle this.

First, Jackson saw all men of color as a potential enemy.

When Governor Claiborne offered the free men of color as a veteran militia, Jackson responded that arming them and putting them into harms way was a good way to prevent them siding with the British.

The free men of colour…will not remain quiet spectators of the interesting contest. They must be for, or against us — distrust them, and you make them your enemies, place confidence in them, and you engage them by every dear and honorable tie to the interest of the country who extends to them equal rights and privileges with white men.

This probably explains the exceptionally high percentage of free men of color serving, relative to population numbers. It is incredibly tempting to read that letter and think Jackson had in mind at least some advance to equal rights and privileges, however there’s a fundamental problem with such a line of thinking.

When Jackson arrived in New Orleans he declared military (martial) law for the first successful time in United States history. He proclaimed it necessary because “those who are not for us are against us, and will be dealt with accordingly” and then “refused to lift his order instituting martial law for months…”.

A Louisiana State senator expressed unease about the ongoing state of martial law in a March 3 newspaper article; Jackson promptly had the senator arrested. When a U.S. District Court Judge demanded that the senator be charged or released, Jackson not only refused, he ordered the judge jailed before banishing him from the city. (When Jackson eventually lifted martial law, the returned judge proceeded to charge him with contempt and levied a thousand-dollar fine, which the “Hero of New Orleans” paid.)

It is worth considering how martial law was Jackson’s preferred method of rule, completely inverted from his letters he sent that said to “place confidence” in the public would gain their loyalty.

He seemed very keen to convince people he had their best interests in mind while he also demanded they pick a side. Martial law stemmed from his complete lack of trust in allowing freedoms. The key to unlocking Jackson’s true feelings seems to be that his concerns over spies and dissent was related to what he saw as a “largely foreign city” (French and Spanish). Jackson fundamentally distrusted New Orleans residents because they were not white like himself.

In other words, what if martial law was Jackson’s manner of dealing with discomfort and protest from a militia of non-whites he planned to defraud?

Don’t forget the Peninsular War kicking off in 1807 between France and Spain meant that by 1809 Cuba expelled Franco-Haitian and French residents. They became refugees escaping to New Orleans, which doubled the population of the city, and tripled the size of its free people of color population two years before the 1811 slave revolt. Martial law may really have been Jackson’s way of dealing with how to maintain white supremacy.

Dozens of “citizens without charges” were put in jail for weeks, not to mention Americans put in jail on spurious basis such as just being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Jackson even tried (unsuccessfully) to enforce blatant military censorship on local newspapers.

Another line of reasoning is that martial law helped obscure a true casualty rate of the American militias, as well as lack of true threat from the British. Most accounts of American deaths seem low, even though hundreds of the “professional” British soldiers had laid down and played dead rather than fight.

Second, Jackson did not have honest intentions.

Of course the freemen were promised equal pay, equal treatment, freedoms and so forth but Jackson appeared to have every interest in bringing non-whites to his side, with no plan of honoring his word to them when he no longer needed them.

In other words, a large U.S. military force of veteran free men of color and slaves was used by Jackson to deliver victory yet his response was to deny those men freedom (as he had promised) at the time of victory and then, as he became U.S. President allegedly in part from the tales of this battle, to strip non-whites in America of their voting rights and perpetuate/expand slavery.

To be fair…while Spanish/French colonial-era slave codes had granted complete rights and equality to a “free man of color” (allowed to be educated, serve in military, own land, business, and even slaves) it was only the March 4, 1812 Louisiana Constitution that removed the right to vote from 2/3 of the people living there. That was long before Jackson would fight a vicious political campaign at the federal level to do them even more harm.

When you think of a battle for “freedom” from British rule, consider the new state’s constitution was so undemocratic and exclusionary, property worth at least $5,000 had to be owned by a white man for him to be a candidate for governor and then he would be chosen by the legislature not voters. So it wasn’t just Jackson trying to build a new aristocratic empire, denying democratic rights to Americans.

However, Jackson was a major influence on the undemocratic and racist direction of America in the mid-1800s. While the British abolished slavery in 1833 (led in 1829 by Mary Prince, an escaped slave from Bermuda), not to mention New York in 1827, or Mexico in 1824, America instead was about to be dragged down by Jackson’s seemingly endless thirst to use his authority for enslaving and massacring non-white Americans.

Extensive administrative and diplomatic experience since Washington was a norm for anyone serving as President of America. Jackson found this unnecessary and dismissed critics who pointed to his lack of time in any Cabinet post or even travel abroad. Jackson had poor writing skills in English alone, so studies in advanced topics such as foreign travel and languages seemed out of the question.

The thing Jackson really leveraged was brutality of his plantations and militancy against non-whites. It was in this context the stories told about the Battle of New Orleans under his martial law and strict control of the press worked to his political advantage.

Although stories of valiant brutality (despite the truth being British soldiers laid down and pretended to be dead) stoked his persona as a war hero by 1824, Jackson failed to navigate the process required to become President. Described as a simple “military chieftain” by his opponents, he proved the title accurate as he initiated a vicious campaign against the newly elected President Adams.

A truly barbaric personality, Jackson spent the next years in bitter opposition to everything and anything American government was doing, framing himself as a benevolent dictator. President Adams, who had been duly voted into office in 1824 under the 12th Amendment, was being challenged to lead the country given vicious and underhanded tactics coming from Jackson’s desire to shut the entire government down if he wasn’t the one put in charge.

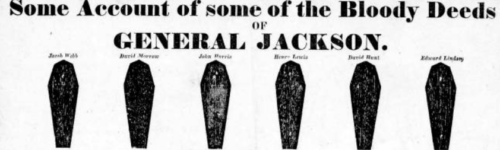

When Jackson ran again for President in 1828, he framed himself a victim of free press and set about trying to take control of political discourse through disinformation tactics. For example, a famous “coffin handbill” depicted American militia men who had been unjustly ordered executed as six black coffins, suggesting that they had been murdered by Jackson. These basically were accurate criticisms of Jackson’s background.

While the press fairly pointed out a record of unjust brutality and lawlessness within Jackson’s only claim to fame, his campaign responded by cooking up a series of total falsehoods to target and destroy his opponent’s character. Jackson basically and openly lied in response to the press pointing out how awful Jackson was, all the while calling himself the real victim.

Jackson delighted in this process, even personally contacting papers with guidelines in what was basically an information warfare campaign by a military chieftain to undermine democracy. Once President, Jackson expanded his war on the press, as I’ve written before:

In 1844 former-President Adams won an eight-year long campaign in the House of Representatives and overturned the Jacksonian bans on free speech, but torture and murder by pro-slavery terrorists continued to rise.

Anyway, PBS has posted an excellent explanation of how free men under Jackson suffered greatly, as he pivoted from credit for this battle to lay the foundation for white-nationalist sentiments and stoke racial divisions in America that remain a challenge today.

Before 1800, free African American men had nominal rights of citizenship. In some places they could vote, serve on juries, and work in skilled trades. But as the need to justify slavery grew stronger, and racism started solidifying, free blacks gradually lost the rights that they did have. Through intimidation, changing laws and mob violence, whites claimed racial supremacy, and increasingly denied blacks their citizenship. And in 1857 the Dred Scott decision formally declared that blacks were not citizens of the United States. […] The concepts of ‘black’ and “white” did not arrive with the first Europeans and Africans, but grew on American soil. During Andrew Jackson’s administration, racist ideas took on new meaning. Jackson brought in the “Age of the Common Man.” Under his administration, working class people gained rights they had not before possessed, particularly the right to vote. But the only people who benefited were white men. Blacks, Indians, and women were not included.

Without taking credit away from the free men of color for their role in the Battle of New Orleans, and stoking up its significance for his own political campaigns, Jackson may never have succeeded in his information war to become President, gag abolitionists and perpetuate slavery, precipitating Civil War.

Jackson’s sentiments greatly foreshadowed not only the Trail of Tears and Civil War but also treatment of American blacks who served in much later wars. Most notable perhaps was the 1921 massacre of WWI veterans in Tulsa by the KKK restarted by President Wilson under the America First campaign.