In multi-factor authentication systems, you typically are dealing with three data categories to establish uniqueness: something you know, something you have or something you are.

While you can create knowledge, create a thing to hold in memory, it is that third category of “being” that often raises the most concern.

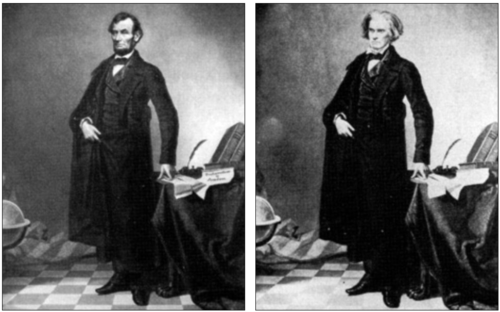

The fakery went quietly along until Stefan Lorant, art director for London Picture Post magazine, noticed a very obvious key to unlock Hick’s puzzle — Lincoln’s mole was on the wrong side of his face. Source: Atlas Obscura

There’s an inherent contradiction in treating a thing you expose everywhere (one that in theory never changes because it is “what you are”), as some kind of uniqueness that can’t be replayed or impersonated by someone else.

Think of it as fingerprints left all over the things in public you have been touching.

This state of “being” tends to be the opposite of secrecy, inherently observable as a function of being, else you would cease to exist.

You’ll be hard pressed to avoid leaving your fingerprints all over the place while at the same time using your fingerprints all over the place to prove you do exist and uniquely.

And lately researchers have been putting into practice a machine version of the very thing seen in Lincoln’s print. For example https://thispersondoesnotexist.com/ will dump out a face that mashes up photos into a “fake” one.

Although here again, for example, you can easily see an error in the lower right corner of an artificially generated image (just like Lincoln’s mole being backwards).

On top of these exposure contradictions in biometric secrecy, there also is a complexity and cost consideration in the biometric business.

Challenge quality is intentionally lowered (look for a couple spots that match instead of every detail and thousands of points) to maintain higher profit/margin. Those economic decisions usually are why we see decades of simple bypasses — a low bar has meant easy impersonation of “what you are”.

Nonetheless, despite the contradictions of exposure and the economics of bypasses, stark warnings still do appear about the lack of security in biometrics.

Consider the “lasting damage” about privacy violations claimed in an analysis of Digital ID applications:

In Zimbabwe, we spoke to people who did not know why the government was transitioning from the old metal ID to a biometric ID. There were theories about the ID system’s connection to national security and surveillance but little knowledge of the government’s intentions or the purpose of collecting biometric data (i.e., unique physical measurements such as fingerprints and iris scans)–which isn’t essential for providing legal identity. This type of data is forever associated with a person’s body, meaning that these systems can lead to privacy violations that cause lasting damage.

Meanwhile in RPI research news, we see the march of science challenging our sense of reality by printing “complete” skin:

Scientists have created 3D-printed skin complete with blood vessels, in an advancement which they hope could one day prevent the body rejecting grafted tissue. The team of researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and Yale School of Medicine combined cells found in human blood vessels with other ingredients including animal collagen, and printed a skin-like material. After a few weeks, the cells started to form into vasculature. The skin was then grafted onto a mouse, and was found to connect with the animal’s vessels.

In related news, scientists also now can “knit” an artificial skin.

“We can sew pouches, create tubes, valves and perforated membranes,” says Nicholas L’Heureux, who led the work at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Bordeaux. “With the yarn, any textile approach is feasible: knitting, braiding, weaving, even crocheting.”

This suggests we are entering an entirely new level of impersonation possibilities, which both are bad (unwanted) and good (wanted). You could knit a new set of fingerprints that even have blood-flowing in them when you’re tired of “being” the old set, or the old set has failed (e.g. too much hand wringing over privacy concerns).

Somehow I doubt the scientists considered as part of their research the impact of medicine bypassing biometric authentication systems, yet we’re clearly approaching a time when you can really do an about face. If I ran marketing I’d sell new skin as giving the finger to biometric authentication vendors.

It all begs the ancient philosophical questions of whether modern quaint notions of authenticity really are something to hold a hard line on (e.g. authorize authenticity policing), or instead we should go back to the focus on harms and virtue ethics.

For a simple quiz I give my CS graduate students studying ethics, would you sooner criminalize actors doing modern voice impersonations or appearance impersonations? Here’s an example of someone doing both, but is it even criminal?